Play Science: What We Know So Far

The Science Is Clear: Play Is Critical for Children and Improves Well-Being for Adults

The capacity to play began evolving millions of years ago; it appears to exist in animals dating back 500 million years. As evolution created ever more complex animals, play capabilities expanded too; humans are the most complex and the most playful of all species.

Today, a diverse body of play research has shown that play is central to leading healthy, productive human lives. No matter your age, play is as important to your mental health as food is to your physical health. Here is the scientific evidence:

1. Babies Need Attunement Play to Learn and Grow

Very early in a baby’s life, parents naturally begin a simple play behavior called attunement, creating the first of many complex play states that will generate crucial neural pathways to support the child throughout life. As they gaze into each other’s eyes, parent and infant create a profound connection — so deep that it synchronizes their neural activity — and they experience a joyful union that leaves them both healthier, happier, and ready to learn and grow together. Attunement in infancy is critical for emotional self-regulation in childhood, and lays the foundation for learning and growth from the toddler through the teen years.

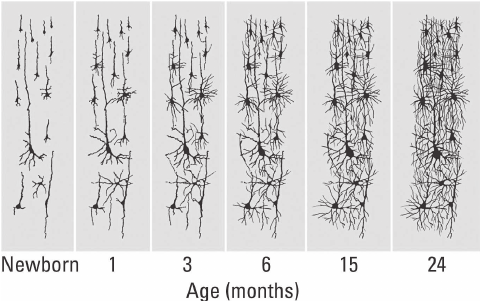

2. Play Builds More Complex Brains

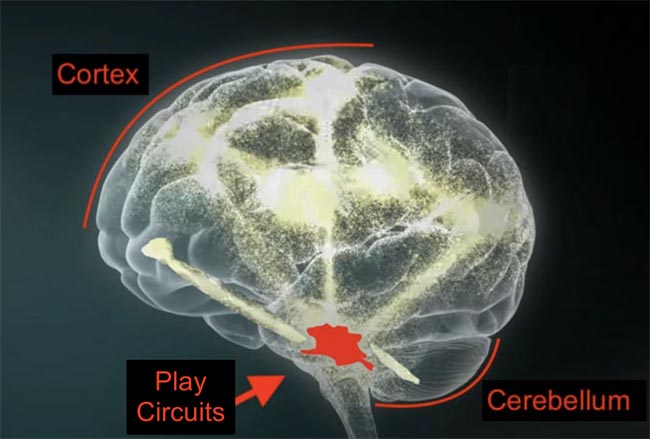

There is no exact blueprint for the cortex — the topmost portion of the brain that makes humans unique among all other creatures. The lower, survival areas of our brains are “pre-programmed,” but human DNA does not contain enough information to create a fully wired cortex. Instead, the cortex “wires” — programs — itself as we grow. Over 70% of that wiring is completed by the time we are three years old. Play is critically important to creating that wiring.

Animal play research shows that the motivation to play is hardwired below the cortex, in the survival centers of the brain. Neuroscience has shown that when the cortex of small mammals is removed, they play just as actively as peers with an intact cortext. But as the animals age, those without a cortex do not develop the ability to relate to their peers and never mate. When threatened by a larger animal, both groups of animals will hide, but those without a cortex remain in hiding long after the threat has passed; they will die of hunger hiding from a predator that left long ago.

Neuroscientists have shown that human brains parallel the structure of those small animals, and that our play begins from the same survival areas of the brain. Play causes the wiring in our cortex to form, the neural pathways that determine how emotionally stable we’ll be and how easily we’ll learn. Young children with severe play deprivation struggle to relate to others and to learn from their life experiences.

3. Babies Learn by Moving

Movement and body play helps sculpt our brains as we grow. Babies begin movement play when they wave their arms and kick. They start rocking, learn to roll over, then get up on their hands and knees and crawl. They stick things in their mouths; they play with their food. Babbling — playing with sound by moving the tongue and lips — becomes intelligible words. Deaf babies will intuitively develop a simple sign language to communicate. Movement play is deeply ingrained in human development, and helps us build our understanding of the world.

All of us gain basic knowledge of our bodies and our environments through movement.

4. Play = Learning

From infancy through their early years, children learn through free play (Gray 2016). Their play circuits are triggered by situations in their environment. A newborn’s cortex begins developing neural pathways in their first months as they learn to move (play with) their fingers, arms, and legs and eventually to move around to explore and learn from their extended environment.

5. Play Develops Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

We all need emotional skills to succeed in school, family, and professional life — skills such as regulating our emotions, communicating effectively with different personality types, defusing conflict, and having empathy for others. These skills are sometimes called “emotional intelligence,” or EQ.

The surest way to help kids develop those fundamental competencies is to give them plenty of time for undirected free play and to foster their play nature. Play with other children is how kids learn to understand the issues and emotions that arise when interacting with peers, and particularly how to regulate their emotions. Through play, they develop the skills they’ll need to excel in teacher-led instruction, along with confidence in their ability to be social (Gray 2013).

Only through play can children develop both cognitive skills (IQ) and emotional skills (EQ); they need both to succeed in school and in life. For kids, play isn’t the opposite of learning. Play is total learning.

6. Kids Need Rough-and-Tumble Play

Rough-and-tumble play is a physical competition to gain some advantage, but it is not fighting. King of the hill, tag, tug-of-war, and simple roughhousing are all good examples. Adults sometimes try to keep kids away from rough-and-tumble play for fear someone will get hurt, but as long as everyone is having fun and no one is violent or threatened, rough-and-tumble play helps kids:

Rough-and-tumble play is a physical competition to gain some advantage, but it is not fighting. King of the hill, tag, tug-of-war, and simple roughhousing are all good examples. Adults sometimes try to keep kids away from rough-and-tumble play for fear someone will get hurt, but as long as everyone is having fun and no one is violent or threatened, rough-and-tumble play helps kids:

- Figure out who they are and what they can do.

- Develop a sense of belonging with their peers.

- Identify their authentic self.

Small mammals deprived of rough-and-tumble play can’t tell friend from foe, overreact to stress, and have smaller brains with fewer connections. Human children show similar patterns.

Kids instinctively know the difference between rough-and-tumble play and real aggression. Play is a shared experience, and happens between friends who stay friends.

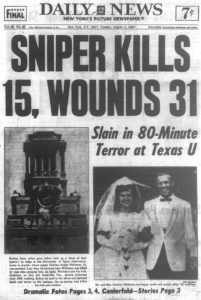

7. Play Deprivation Can Have Tragic Consequences

On August 1, 1966, 25-year-old Charles Whitman killed his wife and his mother, then drove to the University of Texas Austin campus, where he shot and killed another 17 people and wounded 41.

Whitman had never shown a tendency for violence and had no criminal record. He had been an altar boy; he was the youngest American boy to become an Eagle Scout. What went wrong?

Texas governor John Connally assembled a team of international experts to search for causes; Dr. Stuart Brown compiled the behavioral data. The team found that Whitman was raised in an authoritarian, abusive household, where his overbearing father controlled Whitman’s behavior and systematically suppressed his natural playfulness.

The committee concluded that lack of play was a key factor leading to his horrific act. Researchers believed he would have developed the skill, flexibility, and strength to cope with stressful situations without violence if he had enjoyed regular moments of spontaneous play during his childhood.

This conclusion led Dr. Brown to conduct a yearlong review of young men imprisoned for murder, which again showed a significant difference in play histories. Compared to a statewide control group, the men imprisoned for murder were severely play deficient.

Of course, children routinely deprived of free play will not automatically turn to violence. But children who are overly controlled and deprived of free play do develop unhealthy behaviors. By letting children play, by nurturing their natural playfulness and encouraging them to carry that playfulness into adulthood, we help them learn to adapt to social situations and be resilient under stress without lashing out at the world or themselves. At the greatest extreme, play saves lives.

On August 1, 1966, 25-year-old Charles Whitman killed his wife and his mother, then drove to the University of Texas Austin campus, where he shot and killed another 17 people and wounded 41.

Whitman had never shown a tendency for violence and had no criminal record. He had been an altar boy; he was the youngest American boy to become an Eagle Scout. What went wrong?

Texas governor John Connally assembled a team of international experts to search for causes; Dr. Stuart Brown compiled the behavioral data. The team found that Whitman was raised in an authoritarian, abusive household, where his overbearing father controlled Whitman’s behavior and systematically suppressed his natural playfulness.

The committee concluded that lack of play was a key factor leading to his horrific act. Researchers believed he would have developed the skill, flexibility, and strength to cope with stressful situations without violence if he had enjoyed regular moments of spontaneous play during his childhood.

This conclusion led Dr. Brown to conduct a yearlong review of young men imprisoned for murder, which again showed a significant difference in play histories. Compared to a statewide control group, the men imprisoned for murder were severely play deficient.

Of course, children routinely deprived of free play will not automatically turn to violence. But children who are overly controlled and deprived of free play do develop unhealthy behaviors. By letting children play, by nurturing their natural playfulness and encouraging them to carry that playfulness into adulthood, we help them learn to adapt to social situations and be resilient under stress without lashing out at the world or themselves. At the greatest extreme, play saves lives. If he had just been allowed to play ...

8. Play Improves Lives

Making play a regular part of your life is incredibly powerful. Play supports our mental health, improves our ability to relate to others, and increases our drive and hope for the future. When play is missing or inadequate, it can have negative consequences in all of these areas. If you would like to be closer to the left side of the table below, try building more play into your daily or weekly routine for a while. Play won’t magically solve every problem, but it can — and will — give you a more optimistic outlook and mitigate stress levels during challenging life events.

When Life Is … | Play-Filled | Play-Deprived |

|---|---|---|

Trust | Life is experienced as a playground filled with chances to learn | Life is experienced as a proving ground — and often a battleground |

Flexibility | Change brings exploration and new possibilities | Change creates fear and resistance |

Optimism | Well-being and pleasure are expected | Discomfort and disappointment are expected |

Problem-Solving | Problems are acknowledged and often foster skill development | Problems are hidden, denied, or avoided |

Emotional Regulation | Stress is handled with resilience; the response is most often stability | Stress responses are often anger, rage, or withdrawal caused by low self-efficacy |

Perseverance | Motivation is sustained from internal drive, mastery is sought | Motivation dissipates; equivocation, procrastination, and apathy arise

|

Empathy | Others’ feelings are recognized; support is often offered | Others’ feelings are not recognized; discord occurs |

Openness | Life is vital; a strong sense of belonging fosters social cooperation | Life is dull; people become socially withdrawn, often with mild depression |

Belonging | Behaviors are altruistic, leading to teamwork, community creation, and participation | Behaviors are callous, uncooperative, bullying, and self-centered |